Malaria transmission in a warming world

Malaria and Climate Change

Malaria and Climate Change

Woman in Nepal. Photo credit: CIAT Neil Palmer 2012

The health impacts of climate change are related to both extreme events such as floods and droughts but also more complex and long-term direct and indirect impacts on health.

On This Page

- Key Principles of Malaria and Climate Change

- Policy Recommendation on Malaria and Climate Change

- Additional Resources for Malaria and Climate Change

Climate change is altering the transmission of vector-borne diseases (VBDs), including malaria, putting malaria control and elimination efforts at risk all over the world. One main reason is that climate change is creating more suitable conditions for VBDs like malaria. Pathogens, such as the malaria parasite and the dengue virus, develop faster at higher temperatures and longer rainfall spells resulting from climate change can also lead to stagnant water which is critical for mosquito breeding.

Evidence from South Asia suggests that malaria and dengue are increasingly being found in the higher altitude mountainous areas of this region. A quantitative assessment by the World Health Organization (WHO) estimated that climate change may cause an additional 60,000 malaria deaths between 2030 and 2050, even when accounting for economic growth and health progress. It also projects that about 5% of the global malaria cases, or 21 million cases, would be attributable to climate change in 2030.

Long-term climate change takes place alongside complex socio-economic changes including land use change, population growth, urbanization, migration, and economic development. These play an equally important role vis-à-vis malaria. In response, countries need to understand, predict and prevent the impacts of climate change on health and malaria outcomes.

Key Principles of Malaria and Climate Change

Variable and unpredictable impact on infectious diseases

Hotter weather and more erratic rainfall will be a reality even if global climate targets are met. Given that mosquito breeding habits change alongside changes in the climate, millions more will be exposed to malaria and other VBDs because of variable climate conditions. It will be prudent to track the changing climate and its impact on malaria burden in the region.

Climate change can induce migration and increase exposure to pathogens

Malaria will likely move into areas where both people and health systems are not used to fighting the disease. In addition, climate change induced movement of people from areas of high transmission can result in imported cases and potential re-introduction of malaria into low-transmission or malaria-free zones.

Climate change is a “threat multiplier”

Climate change will indirectly exacerbate the malaria risks for already at-risk groups including women and children, and communities living in remote areas. For example, hard-to-reach areas in the Greater Mekong Subregion are often entirely cut off during seasonal heavy rains due to flooding. Also, climate change can alter living patterns. Dry weather brought about by climate change, for instance, will force people to store more water. The storage systems can become breeding grounds for mosquitoes if not managed properly.

Policy Recommendation on Malaria and Climate Change

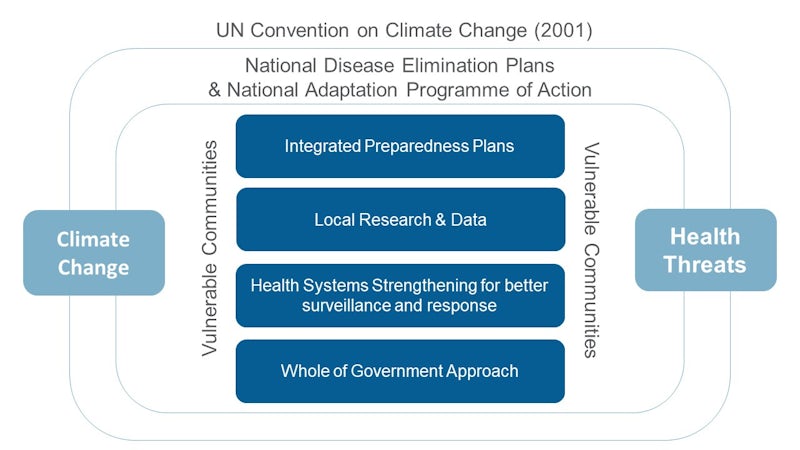

Climate change considerations should be a critical component of strategies for control and elimination of VBDs. Since the impact of climate change will vary from country to country and over time, the response too should be tailored to local conditions.

1. Integrate preparedness plans using climate-related information into national health strategies.

- Use weather information and seasonal forecasts to enhance risk assessment and preparedness for malaria e.g. through the WHO Vulnerability and Adaptation Assessment tool.

- Integrate variables that interact with both the environment and VBDs in disease and transmission modelling.

2. Promote local research on impact of climate change on VBDs and improve surveillance.

The impact of climate change on VBDs will vary across locations and over time. Moreover, the relationship between variables such as temperature and malaria are not linear.

- Strengthen local research and modelling capacity to monitor the potential impact of climate change on VBDs, including at the sub-national level.

3. Strengthen health systems for better surveillance and response.

Health systems strengthening projects must include actions that will strengthen the response to climate sensitive VBDs in specific ways. Core investments in the health sector will protect us from climate change-related health risks including malaria.

- Invest in integrated surveillance mechanisms and information sharing.

4. Promote ‘whole of government’ approaches to effectively deal with impact of climate change on VBDs and health in general.

- Invest in mechanisms that promote coordinated action among health and non-health sectors (particularly agricultural, environmental, and meteorological sectors) and different levels of government.